A Beautiful and Strange Otherness

"When we open ourselves and take in the sorrows of the world, letting them penetrate our insulated hut of the heart, we are both overwhelmed by the grief of the world and in some strange alchemical way, reunited with the aching, shimmering body of the planet. We become acutely aware that there is no “out there;” we share one continuous presence, one shared skin. Our suffering is mutually entangled, the one with the other, as is our healing."

I was recently in the pine forests of Northern Minnesota to teach at the Minnesota Men’s Gathering. I was invited to the gathering to speak about the role of grief as it related to the conference theme: Dark Talk with Screeching Pines: Why Men Listen to Nature’s Voices. The land was familiar to me, shaped by ancient glacial activity as it receded at the end of the last Ice Age. Having lived the first twenty-two years of my life in Wisconsin, I recognized the terrain immediately. It was in my body and it spoke a familiar language.

The first thing I did when I arrived at the conference was to ask Miguel Rivera to introduce me to the Spirit of the Lake. While the land was familiar to me, I was unknown to the place and I wanted to step onto this land in a respectful way. We walked out on the pier and with tobacco and sweet words in Mayan, Lakota, Spanish and English, we said hello and offered our greetings to this place. I brought greetings from the redwoods, the salmon people, madrone and Douglas Firs, the familiars from my coastal Northern California home. In beauty, it had begun.

The first night we stepped immediately into ritual. It was clear to me that these men were carrying something deep and powerful. This was no mere conference, but an established ritual ground whose intention it is to dream and feed a new culture, one invigorated by ancient practices like ritual and renewed by the vital waters of myth and story, poetry and singing. I was walking onto sacred ground. Some part of me felt deeply at home and grateful to find another place devoted to the mending of culture and the culture of mending men’s souls.

I was asked to prepare a couple of talks which would be shared over the week. I realized I had a good deal of material on one topic and that it would probably fill the two times I would be invited to teach. My talk was called, “A Beautiful and Strange Otherness.” The title comes from a passage of human biologist, Paul Shepard that occurred in the course of an interview. He was asked what role the “others” played in our development as a species. The others here referred to the animals, plants, rivers, trees; the entire surrounding field that was the ongoing reflection we encountered for hundreds of thousands of years. Shepard’s response was stunning, ending his thought with a sentence that has captivated me ever since I first read it many years ago. He said, “The grief and sense of loss that we often attribute to a failure in our personality, is actually a feeling of emptiness where a beautiful and strange otherness should have been encountered.”

As is always the case when I share that quote, there is an immediate request to repeat it slowly as everyone scrambles for pen and paper. After I shared the passage, I said, “We could spend the rest of this gathering metabolizing the gravity of this one sentence.”

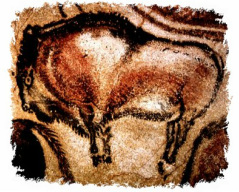

The weight carried by this phrase astonishes me. We were meant to have a life-long engagement with a beautiful and strange otherness. It was meant to be an ongoing presence, not an exception or something that we capture on our cameras while on vacation in Yellowstone or by watching it on the Nature Channel. Shepard spoke adamantly and repeatedly how the others shaped us and made us human; how the lessons of coyote and rabbit, mouse and hawk taught us core values and how to live here in a sustainable way. Animal images were the first to appear in recesses and cave paintings, the first to be conjured in myths and tales. Their ways were integral not only to our survival, but to the very shaping of our souls.

Now, in the shortest wisp of a moment, the perennial conversation has been silenced for the vast majority of us. There are no daily encounters with woods or prairies, with herds of elk or bison, no ongoing connection with manzanita or scrub jay. They myths and stories about the exploits of raven, the courage of mouse, the cleverness of fox have fallen cold. The others have retreated and have essentially vanished from our attention, our minds and our imaginations. What happens to our soul life in the absence of the others? Shepard says that what emerges is a grief-laden emptiness. How true. He was wise, however, to recognize our tendency to attribute the emptiness to a “failure in our personality.”

Nearly every day in my practice, I hear someone talk about feeling empty. But what if this emptiness is more akin to what Shepard is suggesting? What if what we are experiencing is the deep silence, a prolonged absence of birdsong, the scent of sweetgrass, the taste of wild huckleberries, the cry of the red tail hawk or the melancholy call of the loon? What if this emptiness is the great echo in our soul of what it is we expected and did not receive?

“We are born,” wrote psychiatrist R.D. Laing, “as Stone Age children.” Our entire psychic, physical, emotional and spiritual makeup was shaped in the long evolutionary sweep of our species. Our inheritance includes an intimate and permeable exchange with the wild world. It is what we expected. Ecopsychologist Chellis Glendinning calls this original enfoldment in the natural world The Primal Matrix. We were entangled, embedded in this matrix of life and knew the world and ourselves only through this perception. It was an unmediated intimacy with the living world with no trace of separation between the human and the more-than-human world.

What was once a seamless embrace has now become a breach, a tear in our sense of belonging in the world. This rip in the fabric of our belonging is what Glendinning calls our “original trauma.” This trauma carries with it all the recognizable symptoms associated with this psychic injury: chronic anxiety, dissociation, distrust, hyper-vigilance, disconnection, as well as many others. We are left with a profound loneliness and isolation that we rarely acknowledge. It is as if we have completely normalized our condition. And yet, this feeling of separation profoundly affects the range of our reach into the world, the ways we participate in the landscape and sense our allegiance with the living world. Our soul life diminishes, flickers dimly and rather than feeling a kinship with the entire breathing world, we inhabit and defend a small shell of a world, occupying our daily life with what linguist David Hinton calls the “relentless industry of self.”

Sigmund Freud recognized the reduction in our life that accompanies the process of enculturation. He wrote:

Originally the ego includes everything, later it separates off an external world from itself. Our present ego-feeling is, therefore, a shrunken residue of a much more inclusive—indeed all embracing—feeling which corresponded to a once intimate bond between the ego and the world around it.

We did not come here to be a shrunken residue of a formerly intimate life. This “beautiful and strange otherness” was also meant to be seen in one another’s eyes. We too, are meant to embody a vivid and animated life, to live close to our wild souls, our wild bodies and minds. We were meant to dance and sing, play and laugh unselfconsciously, tell stories, make love and take delight in this brief but privileged adventure of incarnation. The wild within and the wild without are kin, the one enlivening the other in a beautiful tango.

When we pause and allow our separation from the living earth to rise, we feel the “grief and sense of loss” that begins Shepard’s phrase. When we open ourselves and take in the sorrows of the world, letting them penetrate our insulated hut of the heart, we are both overwhelmed by the grief of the world and in some strange alchemical way, reunited with the aching, shimmering body of the planet. We become acutely aware that there is no “out there;” we share one continuous presence, one shared skin. Our suffering is mutually entangled, the one with the other, as is our healing.

The question we now hold steadfast in our attention today and every day is: How do we re-enter the deep conversation with the Beautiful and Strange Otherness? I will write about this in Part II.

The first thing I did when I arrived at the conference was to ask Miguel Rivera to introduce me to the Spirit of the Lake. While the land was familiar to me, I was unknown to the place and I wanted to step onto this land in a respectful way. We walked out on the pier and with tobacco and sweet words in Mayan, Lakota, Spanish and English, we said hello and offered our greetings to this place. I brought greetings from the redwoods, the salmon people, madrone and Douglas Firs, the familiars from my coastal Northern California home. In beauty, it had begun.

The first night we stepped immediately into ritual. It was clear to me that these men were carrying something deep and powerful. This was no mere conference, but an established ritual ground whose intention it is to dream and feed a new culture, one invigorated by ancient practices like ritual and renewed by the vital waters of myth and story, poetry and singing. I was walking onto sacred ground. Some part of me felt deeply at home and grateful to find another place devoted to the mending of culture and the culture of mending men’s souls.

I was asked to prepare a couple of talks which would be shared over the week. I realized I had a good deal of material on one topic and that it would probably fill the two times I would be invited to teach. My talk was called, “A Beautiful and Strange Otherness.” The title comes from a passage of human biologist, Paul Shepard that occurred in the course of an interview. He was asked what role the “others” played in our development as a species. The others here referred to the animals, plants, rivers, trees; the entire surrounding field that was the ongoing reflection we encountered for hundreds of thousands of years. Shepard’s response was stunning, ending his thought with a sentence that has captivated me ever since I first read it many years ago. He said, “The grief and sense of loss that we often attribute to a failure in our personality, is actually a feeling of emptiness where a beautiful and strange otherness should have been encountered.”

As is always the case when I share that quote, there is an immediate request to repeat it slowly as everyone scrambles for pen and paper. After I shared the passage, I said, “We could spend the rest of this gathering metabolizing the gravity of this one sentence.”

The weight carried by this phrase astonishes me. We were meant to have a life-long engagement with a beautiful and strange otherness. It was meant to be an ongoing presence, not an exception or something that we capture on our cameras while on vacation in Yellowstone or by watching it on the Nature Channel. Shepard spoke adamantly and repeatedly how the others shaped us and made us human; how the lessons of coyote and rabbit, mouse and hawk taught us core values and how to live here in a sustainable way. Animal images were the first to appear in recesses and cave paintings, the first to be conjured in myths and tales. Their ways were integral not only to our survival, but to the very shaping of our souls.

Now, in the shortest wisp of a moment, the perennial conversation has been silenced for the vast majority of us. There are no daily encounters with woods or prairies, with herds of elk or bison, no ongoing connection with manzanita or scrub jay. They myths and stories about the exploits of raven, the courage of mouse, the cleverness of fox have fallen cold. The others have retreated and have essentially vanished from our attention, our minds and our imaginations. What happens to our soul life in the absence of the others? Shepard says that what emerges is a grief-laden emptiness. How true. He was wise, however, to recognize our tendency to attribute the emptiness to a “failure in our personality.”

Nearly every day in my practice, I hear someone talk about feeling empty. But what if this emptiness is more akin to what Shepard is suggesting? What if what we are experiencing is the deep silence, a prolonged absence of birdsong, the scent of sweetgrass, the taste of wild huckleberries, the cry of the red tail hawk or the melancholy call of the loon? What if this emptiness is the great echo in our soul of what it is we expected and did not receive?

“We are born,” wrote psychiatrist R.D. Laing, “as Stone Age children.” Our entire psychic, physical, emotional and spiritual makeup was shaped in the long evolutionary sweep of our species. Our inheritance includes an intimate and permeable exchange with the wild world. It is what we expected. Ecopsychologist Chellis Glendinning calls this original enfoldment in the natural world The Primal Matrix. We were entangled, embedded in this matrix of life and knew the world and ourselves only through this perception. It was an unmediated intimacy with the living world with no trace of separation between the human and the more-than-human world.

What was once a seamless embrace has now become a breach, a tear in our sense of belonging in the world. This rip in the fabric of our belonging is what Glendinning calls our “original trauma.” This trauma carries with it all the recognizable symptoms associated with this psychic injury: chronic anxiety, dissociation, distrust, hyper-vigilance, disconnection, as well as many others. We are left with a profound loneliness and isolation that we rarely acknowledge. It is as if we have completely normalized our condition. And yet, this feeling of separation profoundly affects the range of our reach into the world, the ways we participate in the landscape and sense our allegiance with the living world. Our soul life diminishes, flickers dimly and rather than feeling a kinship with the entire breathing world, we inhabit and defend a small shell of a world, occupying our daily life with what linguist David Hinton calls the “relentless industry of self.”

Sigmund Freud recognized the reduction in our life that accompanies the process of enculturation. He wrote:

Originally the ego includes everything, later it separates off an external world from itself. Our present ego-feeling is, therefore, a shrunken residue of a much more inclusive—indeed all embracing—feeling which corresponded to a once intimate bond between the ego and the world around it.

We did not come here to be a shrunken residue of a formerly intimate life. This “beautiful and strange otherness” was also meant to be seen in one another’s eyes. We too, are meant to embody a vivid and animated life, to live close to our wild souls, our wild bodies and minds. We were meant to dance and sing, play and laugh unselfconsciously, tell stories, make love and take delight in this brief but privileged adventure of incarnation. The wild within and the wild without are kin, the one enlivening the other in a beautiful tango.

When we pause and allow our separation from the living earth to rise, we feel the “grief and sense of loss” that begins Shepard’s phrase. When we open ourselves and take in the sorrows of the world, letting them penetrate our insulated hut of the heart, we are both overwhelmed by the grief of the world and in some strange alchemical way, reunited with the aching, shimmering body of the planet. We become acutely aware that there is no “out there;” we share one continuous presence, one shared skin. Our suffering is mutually entangled, the one with the other, as is our healing.

The question we now hold steadfast in our attention today and every day is: How do we re-enter the deep conversation with the Beautiful and Strange Otherness? I will write about this in Part II.