Reclaiming Our Indigenous Soul

"The indigenous soul lives close to the ground, to moss, river and loon. It moves in springs and wind, is close to the breath of coyotes. It is scratched on rock walls around the planet, is seen dancing around firelight and is heard in stories told under the canopy of stars. The indigenous soul is the thread of our humanness woven inextricably with the world. Where all things meet and exchange the vitality that is life, there is soul."

For several million years we have been shaped by the landscape, by wind and mist, wolf howl and sunset. We were inseparable from nature and knew ourselves only in relationship with all our kin. We shared this world with an astonishing array of animals, birds, insects and plants, surrounded by trees, rivers and mountains. We were one among many, finding our way in common among those with whom we shared this sentient terrain. The indigenous soul carries the long evolutionary story of our species set intimately in the context of the wild world. It is the part of our psychic life that we hold in communion with the life that moves around us.

It was this setting that gave the soul its shape. Our psychic lives were made here, on the plains, in woodlands, near lakes and hills. Our original spirituality emerged along with a growing awareness that all things were bound together in a seamless web of life. Chief Seattle reminds us and modern physics affirms that, “All things are connected.” When we walk in nature, some piece of us quickens and knows the truth of this fact. We are connected with all things and they are our kin.

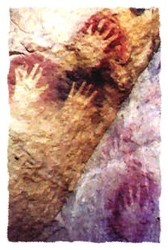

The indigenous soul lives close to the ground, to moss, river and loon. It moves in springs and wind, is close to the breath of coyotes. It is scratched on rock walls around the planet, is seen dancing around firelight and is heard in stories told under the canopy of stars. The indigenous soul is the thread of our humanness woven inextricably with the world. Where all things meet and exchange the vitality that is life, there is soul.

The recovery of the indigenous soul is imperative. We are in serious trouble as a people. Nearly every biological system is in peril: our watersheds, oceans and topsoil are experiencing rapid deterioration. We face a future that will be seriously impacted by radical changes in our climate. We are also witnessing the daily loss of the wild as we encroach ever further into wetlands and forests. We have forgotten our place in the world. And this woe is not confined to us alone; it extends to the others with whom we share this world. Many species find themselves threatened by these changes: grizzlies, blue fin tuna, spotted owls, coral reefs, Atlantic salmon, autumn buttercup, golden-cheeked wood warbler, Baker’s cypress. This list goes on and on. There are 2,269 endangered species in the United States alone. They are caught in a cascading net of sorrows, powerless to change or adapt. We must reconnect with this ancient ground of being that is our indigenous soul and recall that we are all of the earth.

We are living, you and I, with only the remotest memory of life intimately lived with the earth. Our progress has taken us away from the green world and landed us squarely on asphalt and concrete, microchip and mall. My soul cries out from this loss, this ripping us away from the primal matrix. I know I feel different, quieter, when I sit and let the sounds of wind, rain, birdsong and cricket wash my ears with the deep song our ancestors recognized as the eternal music of the world. When I walk in the woods, or along the ocean, my soul comes forward and breathes deeply, sighs and comes once again into contact with the living earth. It is in this state of permeability that I actually feel the world, register its many and varied presences, and come into the full radiance of this shimmering terrain. I am moved daily by the play of light on the hills across the valley, the songs of robins and towhees, and the sweet fragrance of morning dew on the dry grasses of summer.

Laurens van der Post writes, “We cannot, today, recreate the original ‘wilderness man’ in shape, form and habitat. But we can recover him, because he exists in us. He is the foundation in spirit or psyche on which we build, and we are not complete until we have recovered him.”(1) We are not complete until we have recovered this part of our being. The ground of the indigenous soul is the foundation upon which we build our lives in this world. This is the basis of who we are, the root structures that guide our everyday movement through the world, through instincts and emotions, intuitions and sensations. This is a very different perspective from trying to deny, control or repress our natural desires to connect and live within the folds of the world.

Our soul is designed to feel kinship with the living world. Watch children enraptured by the vitality of life found in nature. They become fully absorbed in the moment, a presence that rivals any meditation master. Holding a salamander, a stone, a frog, they are emptied of everything save for what has opened their minds and captured their attentions. Everything about this world engenders awe, a pervasive and encompassing feeling of love for this life: the beauty of wildflowers, the hum of bees and the sweet taste of honey, all cause our spirits to swell with joy.

We have become accustomed to monotony and depression. In fact, the number of people taking anti-depressants has doubled over the last decade.(2) Nearly thirty million individuals are now taking medications to deal with their depression. (Many others medicate with alcohol, drugs, TV, food, shopping or any number of anesthetics for their pain.) As someone who works with many depressed individuals, I know the life-saving quality that these medications can serve. However, the deeper question that we need to be asking is why so many of our people are depressed. How is it that we have shaped a culture that leaves so many of our people feeling empty, flattened and disheartened? Every day I see someone in my office carrying the weight of these symptoms. It crushes the spirit, leaves us breathless and unable to drink in the beauty of the world.

We must come back to life, in both meanings of that phrase: back to that which shaped us and made us thrum with aliveness and back from this state of pre-death where our sense of who we are and what holds meaning has been torn from our hearts by a narrowing of our attention and a preoccupation with survival only.

I know we were made to live here happily. Everything about our makeup says so. We are carriers of connection. Our psychic and physical design makes us a giant receptor site for engagement. We were made to take the world into us, to digest her astonishing beauty with our senses. Then, in the quiet of our inner world of reflection, intuition and thought, in the places where intimacy is registered, our affections are meant to be returned to the world. This erotic leap between our senses and the world deepens our connection and affection for the world. Even something as ordinary as our daily meals provides moments when we can pause and sense this reality. Eating is such a sensuous experience. Let the juice of the peach linger for a bit on your lips. Celebrate the sweetness of the cantaloupe or the salty satisfaction of cashews on your tongue. These are the simple blessings offered to us every day. My poem, “Day to Day Devotions” speaks about this opportunity for engagement.

Imagine making of your life a prayer,

A worship, a devotion. Imagine moving

through the world in celebration

casting alms by the sure presence

of your faith in life.

Imagine waking and rising to

be an invocation, a gifting

in which what is most

precious to you is invited

into the world.

Imagine eating and bathing as

sacramental, a communion with

the sacred other, a remembrance

of all our relations whereby

our own self is given form.

Imagine breathing and walking,

touching and holding to be the

movements of your soul as it

feels its way into your

arms and legs, those

“inlets of soul in our age” as Blake reminds us.

Imagine talking and listening

as rituals of meeting

where who you are is

welcomed into the

heart of another.

Imagine these day to day devotions

as the purest chance you have

of redemption. Imagine

these simple gestures as

God’s sweetest blessing.

I have been intrigued with indigenous cultures for many years. One of the frequently reported comments from those that witnessed these cultures was the amount of laughter, humor and joy they encountered. I want that in my life, in my community, for my son and those others whom I love–joy that is infectious and that keeps our hearts fed during hard times; joy that enables us to step back from the feeding trough of consumerist society. Jean Liedloff, author of the Continuum Concept, has suggested that happiness has ceased to be a condition of being alive and instead has become a goal. I’ll be happy when . . .What? I retire? I get this new TV? I get my shit together? And on and on. This is what we’ve come to call the pursuit of happiness.

This pursuit is endless. We are, as one of my mentors said, climbing the ladder of success only to find it leaning against the wrong building! Living as we do in the belly of a soul-eating culture, we must consistently strive to discover ways to get back to the ground of our indigenous soul. By doing what matters most to the soul, we are drawn closer into our lives. We feel the allure of village life, that genuine experience of community that circulates around a shared commitment to one another’s soul life. The village is where we feel welcomed, where who we are is invited into the conversation and where what we have to offer to the community is received.In the village everyone is “spiritually employed,” meaning everyone is needed and everyone has a particular gift to offer the community. We long to feel a part of a circle that offers this full reception.

We will also feel ourselves responding to the pull of nature and find our feet walking deliberately into the woods and mountains, along singing rivers and blue-green turquoise seas. We find ourselves falling into the arms of the living earth. These primary satisfactions are what feed the soul and satisfy our deepest needs for connection and intimacy with the life around us.

The indigenous soul is immense. That is why we come alive when we move near the energies that inhabit the world: rivers, deserts, mountains, woodlands. Some arc leaps from our being and creates a link with this otherness, reminding us of our closeness to the living world and with one another. Our loneliness is tied up entirely with our loss of contact with these deeper truths. We can never be lonely in this world once we relearn how to continually feel our deep connection with it. When the finches sing, our ears become enamored with their beautiful call, and if we have but ears to hear, we know and feel the corresponding cadence in our soul and offer our song back to the world.

Recovering this deep song in my soul has made all the difference in my existence. I feel at home, at ease in my life and body. The earth is longing for our return. One young woman with whom I worked could not feed herself in a nourishing way. She would consistently deprive herself of good food, as if she was not worthy of nourishment. One day I reached out to her, took her hand, led her out of the office and brought her into the yard outside the building. I cleared away some leaves and grass, revealing the naked earth. I brought her over, knelt down with her and placed her hands on the ground, and I asked her to tell the earth about her struggle with food: A torrent of tears unleashed long lingering grief about her feelings of worthlessness. Her tears fell to the earth and she felt the benevolent pulse of the ground beneath her hands. This was a moment of healing, restoration through the grace of the indigenous soul knowing its deep affiliation with this world. Her relationship to her own indigenous soul was re-established, and she is now the loving mother of her own beautiful, well-fed daughter.

This sweet medicine is available to each of us, offered by the earth without reservation or deserving. There is no earning of this grace, no reward for doing it right. It is a matter of connecting and feeling into the fullness of this constant connection. Our welcome is not predicated on measuring up or being on the right side. It is a matter of intimacy, of relationship with this world as it is.

Somehow along the way, very recently in our human story, a perception emerged that suggested that this world was not holy enough for the soul. The earth was seen as inferior and only heaven or some state of transcendence from this lowly life was acceptable. Our souls were seen or imagined as being ill at ease in the world. This world was a veil of sorrows to be transcended as soon as possible. I simply cannot accept that perception. I feel with my entire being that soul is in love with this magnificent world, that it takes absolute delight in the endless variety of shapes, colors, textures and scents. Jesus himself declared that the kingdom of heaven is spread over the earth, but we do not see it. It is here, adorned in every possible way by nature and this adornment calls the soul out to play. This was the lap from which we emerged and in which we are still held. Herman Hesse writes,

Sometimes, when a bird cries out,

Or the wind sweeps through a tree,

Or a dog howls in a far off farm,

I hold still and listen for a long time.

My soul turns and goes back to the place

Where, a thousand forgotten years ago,

The bird and the blowing wind

Were like me, and were my brothers.

My soul turns into a tree,

And an animal, and a cloud bank.

Then changed and odd it comes home

And asks me questions.

What should I reply?

Herman Hesse

Translated by Robert Bly(3)

Our reply must be to step back into the embrace, into intimate relations with the world where we still feel ourselves turning into trees and animals and cloudbanks. This is not an abstract idea. I am referring to the watersheds and woodlands around our homes, to knowing whose migratory pathways we have entered or have built our homes beneath. Our soul is in love with the singularities, the particular expression of a gnarled cypress, the one-eared feral gray cat on the hillside, this iris and its amazing beard of blue. Love finds itself in the specific. Thus, our efforts to save the world must begin within the scale of what our indigenous soul relates to. We will save the world from our mass overlay of ideologies by loving the world tangibly, with our hands and eyes and our whole bodies. Love is never abstract. It requires bulk and substance, feelings, sensations, quickening in muscle and bone where the anticipation of the other is felt across the surface of the skin.

This is where each of us has an opportunity to decipher how we can experience this love in our own lives. I feel we are coded genetically for relations on a multitude of scales, with the stars, forests and communities, as well as with the smallest circles: a lover, a child or ourselves. We are supremely crafted for intimacy with this world. How else do you think we survived for so many millennia? I talk about intimacy not in some romantic fashion, but in that sense of being penetrated by some great force, engaged in the “constant conversation” that the Persian poet Rumi attests to. This soul dialogue with wind and blackberry binds us to the world.

I was talking with a group of men, engaged in the deep work of initiation, about the role of love in a man’s life and how we have placed such confinement on this capacity in our nature. What I mean by that is that when we love another, we also are being invited to love the world more deeply. Rather than focusing on a single individual, a finite point where love congeals, our loving is meant to move through our beloved and then outward into the greater world itself. Imagine falling in love with the blue of the sky, the scent of honeysuckle. And why not? Why should our love be cloistered, reserved only for others like us? When I leave here, I want to know that I loved this world wholly and by so doing I helped feed the belly of the world; I wasn’t simply a point of extraction, someone who took and took without ever giving back.

I see manifestations of the indigenous soul in eruptions of celebration, enthusiastic expressions of gratitude and rituals of kinship, in shared times of grieving, all acknowledging the abiding connection between the human and the more-than-human world. The annual cycle of rituals that we have developed locally over the years has made it clear that our relationship with the world is deepened and affirmed by these actions. These gatherings strengthen our sense of connection with all life. For example, our annual “Gratitude For All That Is Thanksgiving Ritual” is a three-day celebration that addresses our intimate and primary bond with all creation. We gather in late November as the colors of fall are yielding to the rainy season in California. During our time together we sing, make offerings of clay, share food and stories and we build a beautiful gratitude shrine. Then together, mid-day on Saturday, we enter ritual space where we make offerings of corn meal, agates, clay figures and tobacco in gratitude. This is done one-by-one, much to the delight of the children as they crawl in and out of the shrine where the offerings are placed. On Saturday evening we share a Thanksgiving feast with a bounty of toasts, laughter, wine and delicious desserts brought by every participant. And then we dance for hours in celebration of our togetherness. On Sunday morning we gather the gifts to the earth, to the ancestors and Spirit from the shrine and they are placed into the belly of the earth by the children. It is an amazing celebration that binds the community to one another and deepens our connection with the living earth.

When we pause, even for a brief time and realize our affection for the world, we live a more inclusive and relational life. We remember our place as one among many–at home, sacred and blessed.

Gestures such as these confirm what was self-evident to earth-based traditions: that we are inseparably linked to nature. We ARE nature. In this language older than words(4) we uttered the speech of the indigenous soul and the most notable word in that language was kinship.

The indigenous soul lives in a sea of intimacies, at home with earthworms and eagles, mountain vistas and marshlands. This extensive ground of kinship offered our ancestors a continuing affirmation of the seamless web connecting their spiritual life with the mystery of this world. What we moderns often experience as existential anxiety stands in stark contrast with what is found when the ground of connection is solid beneath our feet. When this wider array of connection is established, we find individuals who feel assured, carrying a soul confidence that enables them to know that they are wanted and desired by the earth. They realize that they carry something of value for the world and it is their spiritual responsibility to offer that medicine. They have entered the great story of life on earth and have remembered who they are, where they belong and what is sacred. I feel this emerging in my own life. My sense of belonging and kinship feels settled, and I feel my soul unwrapping the gifts it came here to offer.

1 Van der Post, Laurens, in A Testament to the Wilderness. The Lapis Press, Santa Monica 1985 Pg. 56.

2 Archives of General Psychiatry, 2009; 66(8): 848-856.

3 Hesse, Herman, in News of the Universe: poems of twofold consciousness. Edited by Robert Bly. Sierra Club Books. San Francisco. 1980 Pg. 86.

4 Jensen, Derrick, A Language Older Than Words. Context Books, NY 2000.

It was this setting that gave the soul its shape. Our psychic lives were made here, on the plains, in woodlands, near lakes and hills. Our original spirituality emerged along with a growing awareness that all things were bound together in a seamless web of life. Chief Seattle reminds us and modern physics affirms that, “All things are connected.” When we walk in nature, some piece of us quickens and knows the truth of this fact. We are connected with all things and they are our kin.

The indigenous soul lives close to the ground, to moss, river and loon. It moves in springs and wind, is close to the breath of coyotes. It is scratched on rock walls around the planet, is seen dancing around firelight and is heard in stories told under the canopy of stars. The indigenous soul is the thread of our humanness woven inextricably with the world. Where all things meet and exchange the vitality that is life, there is soul.

The recovery of the indigenous soul is imperative. We are in serious trouble as a people. Nearly every biological system is in peril: our watersheds, oceans and topsoil are experiencing rapid deterioration. We face a future that will be seriously impacted by radical changes in our climate. We are also witnessing the daily loss of the wild as we encroach ever further into wetlands and forests. We have forgotten our place in the world. And this woe is not confined to us alone; it extends to the others with whom we share this world. Many species find themselves threatened by these changes: grizzlies, blue fin tuna, spotted owls, coral reefs, Atlantic salmon, autumn buttercup, golden-cheeked wood warbler, Baker’s cypress. This list goes on and on. There are 2,269 endangered species in the United States alone. They are caught in a cascading net of sorrows, powerless to change or adapt. We must reconnect with this ancient ground of being that is our indigenous soul and recall that we are all of the earth.

We are living, you and I, with only the remotest memory of life intimately lived with the earth. Our progress has taken us away from the green world and landed us squarely on asphalt and concrete, microchip and mall. My soul cries out from this loss, this ripping us away from the primal matrix. I know I feel different, quieter, when I sit and let the sounds of wind, rain, birdsong and cricket wash my ears with the deep song our ancestors recognized as the eternal music of the world. When I walk in the woods, or along the ocean, my soul comes forward and breathes deeply, sighs and comes once again into contact with the living earth. It is in this state of permeability that I actually feel the world, register its many and varied presences, and come into the full radiance of this shimmering terrain. I am moved daily by the play of light on the hills across the valley, the songs of robins and towhees, and the sweet fragrance of morning dew on the dry grasses of summer.

Laurens van der Post writes, “We cannot, today, recreate the original ‘wilderness man’ in shape, form and habitat. But we can recover him, because he exists in us. He is the foundation in spirit or psyche on which we build, and we are not complete until we have recovered him.”(1) We are not complete until we have recovered this part of our being. The ground of the indigenous soul is the foundation upon which we build our lives in this world. This is the basis of who we are, the root structures that guide our everyday movement through the world, through instincts and emotions, intuitions and sensations. This is a very different perspective from trying to deny, control or repress our natural desires to connect and live within the folds of the world.

Our soul is designed to feel kinship with the living world. Watch children enraptured by the vitality of life found in nature. They become fully absorbed in the moment, a presence that rivals any meditation master. Holding a salamander, a stone, a frog, they are emptied of everything save for what has opened their minds and captured their attentions. Everything about this world engenders awe, a pervasive and encompassing feeling of love for this life: the beauty of wildflowers, the hum of bees and the sweet taste of honey, all cause our spirits to swell with joy.

We have become accustomed to monotony and depression. In fact, the number of people taking anti-depressants has doubled over the last decade.(2) Nearly thirty million individuals are now taking medications to deal with their depression. (Many others medicate with alcohol, drugs, TV, food, shopping or any number of anesthetics for their pain.) As someone who works with many depressed individuals, I know the life-saving quality that these medications can serve. However, the deeper question that we need to be asking is why so many of our people are depressed. How is it that we have shaped a culture that leaves so many of our people feeling empty, flattened and disheartened? Every day I see someone in my office carrying the weight of these symptoms. It crushes the spirit, leaves us breathless and unable to drink in the beauty of the world.

We must come back to life, in both meanings of that phrase: back to that which shaped us and made us thrum with aliveness and back from this state of pre-death where our sense of who we are and what holds meaning has been torn from our hearts by a narrowing of our attention and a preoccupation with survival only.

I know we were made to live here happily. Everything about our makeup says so. We are carriers of connection. Our psychic and physical design makes us a giant receptor site for engagement. We were made to take the world into us, to digest her astonishing beauty with our senses. Then, in the quiet of our inner world of reflection, intuition and thought, in the places where intimacy is registered, our affections are meant to be returned to the world. This erotic leap between our senses and the world deepens our connection and affection for the world. Even something as ordinary as our daily meals provides moments when we can pause and sense this reality. Eating is such a sensuous experience. Let the juice of the peach linger for a bit on your lips. Celebrate the sweetness of the cantaloupe or the salty satisfaction of cashews on your tongue. These are the simple blessings offered to us every day. My poem, “Day to Day Devotions” speaks about this opportunity for engagement.

Imagine making of your life a prayer,

A worship, a devotion. Imagine moving

through the world in celebration

casting alms by the sure presence

of your faith in life.

Imagine waking and rising to

be an invocation, a gifting

in which what is most

precious to you is invited

into the world.

Imagine eating and bathing as

sacramental, a communion with

the sacred other, a remembrance

of all our relations whereby

our own self is given form.

Imagine breathing and walking,

touching and holding to be the

movements of your soul as it

feels its way into your

arms and legs, those

“inlets of soul in our age” as Blake reminds us.

Imagine talking and listening

as rituals of meeting

where who you are is

welcomed into the

heart of another.

Imagine these day to day devotions

as the purest chance you have

of redemption. Imagine

these simple gestures as

God’s sweetest blessing.

I have been intrigued with indigenous cultures for many years. One of the frequently reported comments from those that witnessed these cultures was the amount of laughter, humor and joy they encountered. I want that in my life, in my community, for my son and those others whom I love–joy that is infectious and that keeps our hearts fed during hard times; joy that enables us to step back from the feeding trough of consumerist society. Jean Liedloff, author of the Continuum Concept, has suggested that happiness has ceased to be a condition of being alive and instead has become a goal. I’ll be happy when . . .What? I retire? I get this new TV? I get my shit together? And on and on. This is what we’ve come to call the pursuit of happiness.

This pursuit is endless. We are, as one of my mentors said, climbing the ladder of success only to find it leaning against the wrong building! Living as we do in the belly of a soul-eating culture, we must consistently strive to discover ways to get back to the ground of our indigenous soul. By doing what matters most to the soul, we are drawn closer into our lives. We feel the allure of village life, that genuine experience of community that circulates around a shared commitment to one another’s soul life. The village is where we feel welcomed, where who we are is invited into the conversation and where what we have to offer to the community is received.In the village everyone is “spiritually employed,” meaning everyone is needed and everyone has a particular gift to offer the community. We long to feel a part of a circle that offers this full reception.

We will also feel ourselves responding to the pull of nature and find our feet walking deliberately into the woods and mountains, along singing rivers and blue-green turquoise seas. We find ourselves falling into the arms of the living earth. These primary satisfactions are what feed the soul and satisfy our deepest needs for connection and intimacy with the life around us.

The indigenous soul is immense. That is why we come alive when we move near the energies that inhabit the world: rivers, deserts, mountains, woodlands. Some arc leaps from our being and creates a link with this otherness, reminding us of our closeness to the living world and with one another. Our loneliness is tied up entirely with our loss of contact with these deeper truths. We can never be lonely in this world once we relearn how to continually feel our deep connection with it. When the finches sing, our ears become enamored with their beautiful call, and if we have but ears to hear, we know and feel the corresponding cadence in our soul and offer our song back to the world.

Recovering this deep song in my soul has made all the difference in my existence. I feel at home, at ease in my life and body. The earth is longing for our return. One young woman with whom I worked could not feed herself in a nourishing way. She would consistently deprive herself of good food, as if she was not worthy of nourishment. One day I reached out to her, took her hand, led her out of the office and brought her into the yard outside the building. I cleared away some leaves and grass, revealing the naked earth. I brought her over, knelt down with her and placed her hands on the ground, and I asked her to tell the earth about her struggle with food: A torrent of tears unleashed long lingering grief about her feelings of worthlessness. Her tears fell to the earth and she felt the benevolent pulse of the ground beneath her hands. This was a moment of healing, restoration through the grace of the indigenous soul knowing its deep affiliation with this world. Her relationship to her own indigenous soul was re-established, and she is now the loving mother of her own beautiful, well-fed daughter.

This sweet medicine is available to each of us, offered by the earth without reservation or deserving. There is no earning of this grace, no reward for doing it right. It is a matter of connecting and feeling into the fullness of this constant connection. Our welcome is not predicated on measuring up or being on the right side. It is a matter of intimacy, of relationship with this world as it is.

Somehow along the way, very recently in our human story, a perception emerged that suggested that this world was not holy enough for the soul. The earth was seen as inferior and only heaven or some state of transcendence from this lowly life was acceptable. Our souls were seen or imagined as being ill at ease in the world. This world was a veil of sorrows to be transcended as soon as possible. I simply cannot accept that perception. I feel with my entire being that soul is in love with this magnificent world, that it takes absolute delight in the endless variety of shapes, colors, textures and scents. Jesus himself declared that the kingdom of heaven is spread over the earth, but we do not see it. It is here, adorned in every possible way by nature and this adornment calls the soul out to play. This was the lap from which we emerged and in which we are still held. Herman Hesse writes,

Sometimes, when a bird cries out,

Or the wind sweeps through a tree,

Or a dog howls in a far off farm,

I hold still and listen for a long time.

My soul turns and goes back to the place

Where, a thousand forgotten years ago,

The bird and the blowing wind

Were like me, and were my brothers.

My soul turns into a tree,

And an animal, and a cloud bank.

Then changed and odd it comes home

And asks me questions.

What should I reply?

Herman Hesse

Translated by Robert Bly(3)

Our reply must be to step back into the embrace, into intimate relations with the world where we still feel ourselves turning into trees and animals and cloudbanks. This is not an abstract idea. I am referring to the watersheds and woodlands around our homes, to knowing whose migratory pathways we have entered or have built our homes beneath. Our soul is in love with the singularities, the particular expression of a gnarled cypress, the one-eared feral gray cat on the hillside, this iris and its amazing beard of blue. Love finds itself in the specific. Thus, our efforts to save the world must begin within the scale of what our indigenous soul relates to. We will save the world from our mass overlay of ideologies by loving the world tangibly, with our hands and eyes and our whole bodies. Love is never abstract. It requires bulk and substance, feelings, sensations, quickening in muscle and bone where the anticipation of the other is felt across the surface of the skin.

This is where each of us has an opportunity to decipher how we can experience this love in our own lives. I feel we are coded genetically for relations on a multitude of scales, with the stars, forests and communities, as well as with the smallest circles: a lover, a child or ourselves. We are supremely crafted for intimacy with this world. How else do you think we survived for so many millennia? I talk about intimacy not in some romantic fashion, but in that sense of being penetrated by some great force, engaged in the “constant conversation” that the Persian poet Rumi attests to. This soul dialogue with wind and blackberry binds us to the world.

I was talking with a group of men, engaged in the deep work of initiation, about the role of love in a man’s life and how we have placed such confinement on this capacity in our nature. What I mean by that is that when we love another, we also are being invited to love the world more deeply. Rather than focusing on a single individual, a finite point where love congeals, our loving is meant to move through our beloved and then outward into the greater world itself. Imagine falling in love with the blue of the sky, the scent of honeysuckle. And why not? Why should our love be cloistered, reserved only for others like us? When I leave here, I want to know that I loved this world wholly and by so doing I helped feed the belly of the world; I wasn’t simply a point of extraction, someone who took and took without ever giving back.

I see manifestations of the indigenous soul in eruptions of celebration, enthusiastic expressions of gratitude and rituals of kinship, in shared times of grieving, all acknowledging the abiding connection between the human and the more-than-human world. The annual cycle of rituals that we have developed locally over the years has made it clear that our relationship with the world is deepened and affirmed by these actions. These gatherings strengthen our sense of connection with all life. For example, our annual “Gratitude For All That Is Thanksgiving Ritual” is a three-day celebration that addresses our intimate and primary bond with all creation. We gather in late November as the colors of fall are yielding to the rainy season in California. During our time together we sing, make offerings of clay, share food and stories and we build a beautiful gratitude shrine. Then together, mid-day on Saturday, we enter ritual space where we make offerings of corn meal, agates, clay figures and tobacco in gratitude. This is done one-by-one, much to the delight of the children as they crawl in and out of the shrine where the offerings are placed. On Saturday evening we share a Thanksgiving feast with a bounty of toasts, laughter, wine and delicious desserts brought by every participant. And then we dance for hours in celebration of our togetherness. On Sunday morning we gather the gifts to the earth, to the ancestors and Spirit from the shrine and they are placed into the belly of the earth by the children. It is an amazing celebration that binds the community to one another and deepens our connection with the living earth.

When we pause, even for a brief time and realize our affection for the world, we live a more inclusive and relational life. We remember our place as one among many–at home, sacred and blessed.

Gestures such as these confirm what was self-evident to earth-based traditions: that we are inseparably linked to nature. We ARE nature. In this language older than words(4) we uttered the speech of the indigenous soul and the most notable word in that language was kinship.

The indigenous soul lives in a sea of intimacies, at home with earthworms and eagles, mountain vistas and marshlands. This extensive ground of kinship offered our ancestors a continuing affirmation of the seamless web connecting their spiritual life with the mystery of this world. What we moderns often experience as existential anxiety stands in stark contrast with what is found when the ground of connection is solid beneath our feet. When this wider array of connection is established, we find individuals who feel assured, carrying a soul confidence that enables them to know that they are wanted and desired by the earth. They realize that they carry something of value for the world and it is their spiritual responsibility to offer that medicine. They have entered the great story of life on earth and have remembered who they are, where they belong and what is sacred. I feel this emerging in my own life. My sense of belonging and kinship feels settled, and I feel my soul unwrapping the gifts it came here to offer.

1 Van der Post, Laurens, in A Testament to the Wilderness. The Lapis Press, Santa Monica 1985 Pg. 56.

2 Archives of General Psychiatry, 2009; 66(8): 848-856.

3 Hesse, Herman, in News of the Universe: poems of twofold consciousness. Edited by Robert Bly. Sierra Club Books. San Francisco. 1980 Pg. 86.

4 Jensen, Derrick, A Language Older Than Words. Context Books, NY 2000.