Redwood Speech, Watershed Prayers: The poetics of place

"My language must be redwood speech, watershed prayers, oak savannah, coupled in an erotic way with fog, heat, wind, rain and hills, sweetgrass and jackrabbits, wild iris and ocean current. My land is my language and only then can my longing for eloquence by granted. Until then I will fumble and fume and ache for a style of speaking that tells you who I am."

“Getting intimate with nature and knowing our own wild natures is a matter of going face to face many times.”

~Gary Snyder

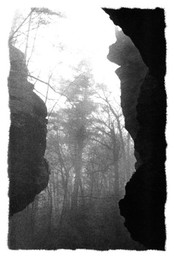

Place, to indigenous cultures and the indigenous soul, is a living presence. Familiar watering holes, majestic mountains, sacred groves of trees, painted rocks and caves where initiations were held, added another dimension to life that is quite foreign to modern consciousness. To live within a sentient geography is to find oneself embedded in a rich and engaging terrain; a land that speaks. To our ancestors, and many indigenous cultures today, the landscape was another voice, a territory imbued with mystery and power. What this offered was another way to encounter the sacred and to enliven the imagination. This fertile exchange between place and psyche established a bond with the land, which, in turn, created an ethos of respect for the land. When the ground holds value, when it is the dwelling place of the spirits and the ancestors, when magic swirls through the canyons and across the plains, the relationship between the people and the land becomes sacramental.

Place is sensual, particular, felt as a presence offering itself to us for connection and spiritual sustenance. In traditional cultures, specific and revered places were saturated with stories, the ground filled with mythological rumblings, for example, the well-known storylines found in the landscape in the Dreamtime myths of the Aboriginal peoples of Australia. Likewise, the Western Apache in Arizona can name hundreds of sites where events took place “in the before time.” To their ancestors, these pathways marked the ways of survival. They led to water and food sources, but even more, they also provided a palpable way of encountering the sacred through geography. To know the world this way, as a living icon, is to know in your body that you are walking upon holy ground. The Aboriginal peoples knew this quality as djang. James Cowen explains what this word meant:

For them djang embodies a special power that can be felt only by those susceptible to its presence. In this way my nomad friends are able to journey from one place to another without ever feeling that they are leaving their homeland. What they feel in the earth, what they hear in the trees are the primordial whispers emanating from an ancient source. And it is this source, linked as it is to the Dreaming, that they acknowledge each time they feel the presence of the djang in the earth under their feet.

Two days after my fortieth birthday I made my way to Armstrong Woods in Guerneville, a small town located about 10 miles from the Pacific Ocean in Northern California. The town is situated on the Russian River, a beautiful waterway that begins some ninety miles to the north. From every perspective you see the tall ones, the redwoods that tower above the valley floor, and during the winter these trees draw an amazing amount of water out of our storms. The town was named after George Guerne, a man who made his mark in the timber industry late in the 1800′s. At that time great stands of redwoods covered most of this area. Now, this woods, set aside as a nature preserve by Colonel James Armstrong in the 1880′s, is one of the last remaining old-growth redwood groves in Sonoma County.

It had been raining hard for the previous few days and on this day the rains persisted. I had been planning this pilgrimage for a long time and when I woke that morning the heavy rains disappointed me. I lay in bed for a while, unsure of what to do, but finally I decided I had to go anyway. I gathered my gear and got in my truck for the drive to Armstrong. It poured all during the forty-minute journey to my destination.

When I pulled into the parking lot of the woods, it was deserted. The heavy weather had made a visit unappealing to others and so I had the old ones to myself. These trees, sequoia sempervirens, are among the oldest living beings on the planet. They can grow over 300 feet high and live for over 2000 years. I came to a stop and turned off the truck. The moment I did, the rain stopped and the sun appeared.

I got out of the truck and made my way through puddles and mud to the trailhead. Since it was late January, the air was cold, and the mist was high in the treetops, adding to the sudden brilliance and beauty of the day. The ground was saturated and I had to make my way slowly down the path. The fragrance in the woods was musty, earthy, rich with the smell of decay and growth, both at the same time. Each tree carried a profusion of jeweled droplets suspended from its branches. I came to one old giant known as “Parson’s Tree,” and gazed up toward its peak. Some 300 feet high, out of my sight, it broke into the open. But down here at its base, I was the recipient of the most exquisite shower of gems. Each drop that fell from the tree carried the sun’s light, came to the body of the earth pulled by the force of gravity and offered itself to the earth as a blessing. I was mesmerized for a long time, drinking in the beauty of this combination of water and light. In deep gratitude I reached out to touch the skin of this elder. Still I knew I had to continue on, not knowing what I was searching for.

Deeper into the woods I went, enjoying the profound silence that the woods offered to me on that day. Even the bird life was subdued. The occasional blue jay announced its presence with a loud bark, but other than the sound of water running in the creek beds, I was walking in silence.

At one point in my sauntering, I came to a redwood with one of the familiar natural openings often featured in pictures of these trees, openings deep enough to enter and stand inside, like a natural cave in the tree trunk. I felt moved to do so now. I stepped down a foot or so to the inner forest floor and stood there surrounded on three sides by the living membrane of this enormous presence. In this stillness, where only my breathing was audible, I heard another voice. Clearly and distinctly the voice said, “I am the Buddha.” I waited quietly and heard the words repeated. “I am the Buddha. This is the dharma and this is your sangha.”

I recognized the words and their meanings. I myself had not spent much time studying Buddhist’s teachings but was aware of these specific terms. The Buddha was the teacher, the dharma was the teaching and the sangha was the community that protected the student and provided the student with support and spiritual encouragement. I could only surmise that these words were coming from this ancient redwood. This old one was the Buddha, was the teacher; the forest and its complex interplay of kingdoms and phyla, species and families was the teaching and the community of sorrel and ferns, bay laurels, Douglas firs and redwoods, creeks and stones, mushrooms and lichen, live oaks and blue jays were indeed, my spiritual community.

I stood motionless to see if the message would be continued. I finally responded and said that I understood the message. Despite the brevity of this redwood’s speech, it was profound. I had never heard nature speak so directly. I’d had moments of intuition or images that conveyed a meaningful exchange but nothing this tangible. And so I stood a long time in the darkness of the tree, within this great being’s body, feeling as though I was wrapped within its essence.

For the next few days I thought about this encounter. This redwood’s speech was so intelligent. Somehow, in some way, it knew to use those exact words. I say that because I am so quick to question the legitimacy of mysterious messages from the spirit world, particularly experiences that are outside the familiar. When the tree chose to speak to me in those words, Buddha, dharma and sangha, it forced me to recognize that the origin of this thought was outside my own consciousness because I would never have used those terms to speak to myself. That thought sent me into a period of wondering about the link between the outer world and myself, a link that I previously had thought was less definitive. However, this experience revealed to me that perhaps the passage between outer and inner was more porous than I had known, than I had been led to believe. Perhaps I am known by the outer world in ways that I had not permitted myself to imagine before.

What was equally important, however, was the event itself and the teaching it carried for me. For far too long we have been detached from nature, from the particulars of the world and her ways of instructing us in how to be a part of the mosaic of life. This knowing is what made our ancestors human in the best sense of the word. “Human” shares the same root origins as “humus,” meaning “of the earth.” Despite all our fantasies of transcendence, resurrection and ascension, despite all our technologies that separate us and insulate us from the sensual world, we are creatures of this earth and our substance is informed by the speech of the world.

I go back often to visit this particular redwood tree with a feeling of friendship and a growing familiarity, realizing that I am hungry for a language that conveys the truth of our bond with the world. Traditional cultures rarely had words that specified generalities like “tree.” Instead they had ways of identifying an individual presence—a specific tree—in the woods. This language of particularity generates a much more sensuous relationship due to the simple fact that naming requires knowing. Conversely, I think of how little time we spend in the woods, along riverbanks, in the hills and mountains. How can we come to know the individualities that exist in the world without time and patience, without attention and relationship? It may be that much of what the soul suffers from is directly related to this severing of its vital connection with the animate world.

When we create an intimate relationship with place, it becomes for us a refuge. This communion offers us a more thorough expression of our innate complexity. Our entire biological structure is designed for engagement with the world. Every sense organ is a gateway for encounter and through this exchange we achieve a greater definition of who we are. The senses are the means by which our bond with the world is consummated and made sacramental. The radical genius William Blake said, “Man has no Body distinct from his Soul for that call’d Body is a portion of Soul discern’d by the five Senses, the chief inlets of Soul in this age.” It is through the blood and sensuality of this flesh that we become incarnate. Till then, till we know that our place is in the world and that our bodies emerged from this earth, we cannot know who we are.

Language too, is rooted to place, to the land. Our imagination is shaped by landscape and topography. Language can either reflect the abundance, the richness of our belonging to a complex and vital community of life or it can reflect a poverty borne of exile.

I am enthralled with the language of indigenous people. Not only does it carry a beauty in its sound, but also the words themselves reflect an unbroken arc between the speaker and his or her surroundings. In many of these languages there is no dichotomy, no separation that strands the human in a point of separation as a cold observer. When a Diné or an Inuit man or woman speak, the cosmos is imminent, not abstracted or referenced. There is seldom the separation between subject and object that we find in our English language. In most traditional speech, there is a continuity of relations that is evident within the structure of the language. The Diné or Navajo language flows in ways that keep relations between everything alive. This is hard for us to comprehend, but it is invaluable for us to know that there are other ways of knowing the world. For example, the Kalahari Bushmen possess an onomatopoetic language that is as close to the sensual world as possible, its cadences mirroring the sounds of the living earth—rain, bird calls. The complex clicks of their speech mimic the rhythms of the actual life around them so that they are constantly immersed in the surrounding terrain.

I feel a deep grief when I think about how far we have deviated from the intimacy we once knew with the earth. Sitting here along the northern coast of California while my wife gathers sweetgrass, I see a tree with a golden ladder rising from its base. A fungus has emerged from this dying elder, an enormous Monterey Pine, and this stairway arises from its decay, orchestrating a new beauty. The sun is illuminating the new growth and it offers itself to me with a radiance that makes me think of Jacob and his celestial stairway.

I have been trying to place myself back into the world, as if I could leave it! Yet, spiritually that is what my culture has taught me to do. I carry a deep conditioning shaped by two thousand years of images, stories and ideals that renders life here on earth as some form of sentence to be commuted through death. We console ourselves with the deaths of those we love by saying that they are now in a better place. The earth is to be transcended: heaven is the better world that will somehow make up for the pain and sorrow of time spent here, our final reward, as it were. I find this offensive and could never believe that the Jesus I know would have ever felt such contempt for the earth. This was the man who constantly referred to the earth, to her creatures and the growing things as examples in his teachings. This was the man who retreated to the wilderness on a number of occasions to gather himself back to himself. Nature, the wild, the world contained and held him.

The wild undoubtedly shaped our original words: imitations of animal sounds, wind, thunder, the music of ocean and river. This lustrous blend of sounds quickened the imagination of our ancestors and, as I said above, even a cursory glance at tribal language reveals a richly textured, complex syntax of metaphor and imagery deeply imbued with the surrounding world. In the Amazon, for example, language is riddled with metaphors of the jungle to express a multitude of situations and aspects in the lives of the people. Jay Griffiths writes, “Metaphor is where language is most wild, spirited and free, leaping boundaries, and it may be no surprise that Amazonian languages can be as matted and dense with metaphor as the forest is tangly with vegetation. The Amazon seems a place of boundless allusion, this unfenced wild, where meaning is twined within meaning; words couple and double, knotted together.” Our modern lexicon, however, reveals an erosion in our formerly flowering language. We are now speaking in acronyms, abbreviations, texting our words through phones and other devices. My feeling is that as our senses are deprived of the multiple cadences from a living world, so too does our language atrophy. We are left with bare rhetoric instead of a kind of speech that can bring us to tears or into symmetry with the many others with whom we share the world.

In a very real way language and place are synonymous. Words reflect what we inhabit, where we dwell. Thomas Berry said that our imagination is only as rich as the diversity of the life around us. If we inhabit a terrain of microchips, cell phones and video monitors, we speak two-dimensionally, abstractly because there is nothing sensual about these realities.

If, on the other hand, our daily round includes sunlight, fragrances from the green earth, songbirds, tastes of berries picked from the bush, then our sensual minds stir and the words become as richly textured as the terrain. Our language has an ecology and it is as varied as the experiences it is given. Jay Griffiths speaks to this in her book, Wild: An Elemental Journey, “All languages have long aspired to echo the wild world that gave them growth and many indigenous peoples say that their words for creatures are imitations of their calls. According to phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty, language ‘is the very voice of the trees, the waves, the forest.’” (pg 25. Wild)

Oral traditions are metaphorical and creative, filled with rich imagery. Stories were held in memory, that is, by heart, and the wisdom was continuous from generation to generation. We have a hard time memorizing our social security number let alone a phenologic account of a living system. What migrates when? What is ripe now? When do we relocate to the winter grounds? How do we prepare the acorns? How do we resolve conflict? How does one become a man or a woman? Stories were the carriers of this wisdom and the words used to transport the stories were alive with meaning and significance.

I want to see our words jump off the ground, erupt from a sensual earth, musty, humid, gritty. I want to taste words like honey, sweet and dripping with eternity. I want to hear words coming from my mouth and your mouth that are so beautiful that we wince with joy at their departure and arrival. I want to touch words that carry weight and substance, words that have shape and body, curve and tissue. I want to feel what we say as though the words were holy utterances surfacing from a pool where the gods drink. What if our words could once again echo the larger reality of the sacred and not solely the world of economics? But that would take an act of remembrance, a slowing downward into a state of presence, awareness and being. And this means being in the world. Enough of this talk that makes us strangers! I want to know I belong here. And if my words can say to you that I am a man of this earth, this particular piece of earth, then I will feel like I have arrived. My language must be redwood speech, watershed prayers, oak savannah, coupled in an erotic way with fog, heat, wind, rain and hills, sweetgrass and jackrabbits, wild iris and ocean current. My land is my language and only then can my longing for eloquence by granted. Until then I will fumble and fume and ache for a style of speaking that tells you who I am.

~Gary Snyder

Place, to indigenous cultures and the indigenous soul, is a living presence. Familiar watering holes, majestic mountains, sacred groves of trees, painted rocks and caves where initiations were held, added another dimension to life that is quite foreign to modern consciousness. To live within a sentient geography is to find oneself embedded in a rich and engaging terrain; a land that speaks. To our ancestors, and many indigenous cultures today, the landscape was another voice, a territory imbued with mystery and power. What this offered was another way to encounter the sacred and to enliven the imagination. This fertile exchange between place and psyche established a bond with the land, which, in turn, created an ethos of respect for the land. When the ground holds value, when it is the dwelling place of the spirits and the ancestors, when magic swirls through the canyons and across the plains, the relationship between the people and the land becomes sacramental.

Place is sensual, particular, felt as a presence offering itself to us for connection and spiritual sustenance. In traditional cultures, specific and revered places were saturated with stories, the ground filled with mythological rumblings, for example, the well-known storylines found in the landscape in the Dreamtime myths of the Aboriginal peoples of Australia. Likewise, the Western Apache in Arizona can name hundreds of sites where events took place “in the before time.” To their ancestors, these pathways marked the ways of survival. They led to water and food sources, but even more, they also provided a palpable way of encountering the sacred through geography. To know the world this way, as a living icon, is to know in your body that you are walking upon holy ground. The Aboriginal peoples knew this quality as djang. James Cowen explains what this word meant:

For them djang embodies a special power that can be felt only by those susceptible to its presence. In this way my nomad friends are able to journey from one place to another without ever feeling that they are leaving their homeland. What they feel in the earth, what they hear in the trees are the primordial whispers emanating from an ancient source. And it is this source, linked as it is to the Dreaming, that they acknowledge each time they feel the presence of the djang in the earth under their feet.

Two days after my fortieth birthday I made my way to Armstrong Woods in Guerneville, a small town located about 10 miles from the Pacific Ocean in Northern California. The town is situated on the Russian River, a beautiful waterway that begins some ninety miles to the north. From every perspective you see the tall ones, the redwoods that tower above the valley floor, and during the winter these trees draw an amazing amount of water out of our storms. The town was named after George Guerne, a man who made his mark in the timber industry late in the 1800′s. At that time great stands of redwoods covered most of this area. Now, this woods, set aside as a nature preserve by Colonel James Armstrong in the 1880′s, is one of the last remaining old-growth redwood groves in Sonoma County.

It had been raining hard for the previous few days and on this day the rains persisted. I had been planning this pilgrimage for a long time and when I woke that morning the heavy rains disappointed me. I lay in bed for a while, unsure of what to do, but finally I decided I had to go anyway. I gathered my gear and got in my truck for the drive to Armstrong. It poured all during the forty-minute journey to my destination.

When I pulled into the parking lot of the woods, it was deserted. The heavy weather had made a visit unappealing to others and so I had the old ones to myself. These trees, sequoia sempervirens, are among the oldest living beings on the planet. They can grow over 300 feet high and live for over 2000 years. I came to a stop and turned off the truck. The moment I did, the rain stopped and the sun appeared.

I got out of the truck and made my way through puddles and mud to the trailhead. Since it was late January, the air was cold, and the mist was high in the treetops, adding to the sudden brilliance and beauty of the day. The ground was saturated and I had to make my way slowly down the path. The fragrance in the woods was musty, earthy, rich with the smell of decay and growth, both at the same time. Each tree carried a profusion of jeweled droplets suspended from its branches. I came to one old giant known as “Parson’s Tree,” and gazed up toward its peak. Some 300 feet high, out of my sight, it broke into the open. But down here at its base, I was the recipient of the most exquisite shower of gems. Each drop that fell from the tree carried the sun’s light, came to the body of the earth pulled by the force of gravity and offered itself to the earth as a blessing. I was mesmerized for a long time, drinking in the beauty of this combination of water and light. In deep gratitude I reached out to touch the skin of this elder. Still I knew I had to continue on, not knowing what I was searching for.

Deeper into the woods I went, enjoying the profound silence that the woods offered to me on that day. Even the bird life was subdued. The occasional blue jay announced its presence with a loud bark, but other than the sound of water running in the creek beds, I was walking in silence.

At one point in my sauntering, I came to a redwood with one of the familiar natural openings often featured in pictures of these trees, openings deep enough to enter and stand inside, like a natural cave in the tree trunk. I felt moved to do so now. I stepped down a foot or so to the inner forest floor and stood there surrounded on three sides by the living membrane of this enormous presence. In this stillness, where only my breathing was audible, I heard another voice. Clearly and distinctly the voice said, “I am the Buddha.” I waited quietly and heard the words repeated. “I am the Buddha. This is the dharma and this is your sangha.”

I recognized the words and their meanings. I myself had not spent much time studying Buddhist’s teachings but was aware of these specific terms. The Buddha was the teacher, the dharma was the teaching and the sangha was the community that protected the student and provided the student with support and spiritual encouragement. I could only surmise that these words were coming from this ancient redwood. This old one was the Buddha, was the teacher; the forest and its complex interplay of kingdoms and phyla, species and families was the teaching and the community of sorrel and ferns, bay laurels, Douglas firs and redwoods, creeks and stones, mushrooms and lichen, live oaks and blue jays were indeed, my spiritual community.

I stood motionless to see if the message would be continued. I finally responded and said that I understood the message. Despite the brevity of this redwood’s speech, it was profound. I had never heard nature speak so directly. I’d had moments of intuition or images that conveyed a meaningful exchange but nothing this tangible. And so I stood a long time in the darkness of the tree, within this great being’s body, feeling as though I was wrapped within its essence.

For the next few days I thought about this encounter. This redwood’s speech was so intelligent. Somehow, in some way, it knew to use those exact words. I say that because I am so quick to question the legitimacy of mysterious messages from the spirit world, particularly experiences that are outside the familiar. When the tree chose to speak to me in those words, Buddha, dharma and sangha, it forced me to recognize that the origin of this thought was outside my own consciousness because I would never have used those terms to speak to myself. That thought sent me into a period of wondering about the link between the outer world and myself, a link that I previously had thought was less definitive. However, this experience revealed to me that perhaps the passage between outer and inner was more porous than I had known, than I had been led to believe. Perhaps I am known by the outer world in ways that I had not permitted myself to imagine before.

What was equally important, however, was the event itself and the teaching it carried for me. For far too long we have been detached from nature, from the particulars of the world and her ways of instructing us in how to be a part of the mosaic of life. This knowing is what made our ancestors human in the best sense of the word. “Human” shares the same root origins as “humus,” meaning “of the earth.” Despite all our fantasies of transcendence, resurrection and ascension, despite all our technologies that separate us and insulate us from the sensual world, we are creatures of this earth and our substance is informed by the speech of the world.

I go back often to visit this particular redwood tree with a feeling of friendship and a growing familiarity, realizing that I am hungry for a language that conveys the truth of our bond with the world. Traditional cultures rarely had words that specified generalities like “tree.” Instead they had ways of identifying an individual presence—a specific tree—in the woods. This language of particularity generates a much more sensuous relationship due to the simple fact that naming requires knowing. Conversely, I think of how little time we spend in the woods, along riverbanks, in the hills and mountains. How can we come to know the individualities that exist in the world without time and patience, without attention and relationship? It may be that much of what the soul suffers from is directly related to this severing of its vital connection with the animate world.

When we create an intimate relationship with place, it becomes for us a refuge. This communion offers us a more thorough expression of our innate complexity. Our entire biological structure is designed for engagement with the world. Every sense organ is a gateway for encounter and through this exchange we achieve a greater definition of who we are. The senses are the means by which our bond with the world is consummated and made sacramental. The radical genius William Blake said, “Man has no Body distinct from his Soul for that call’d Body is a portion of Soul discern’d by the five Senses, the chief inlets of Soul in this age.” It is through the blood and sensuality of this flesh that we become incarnate. Till then, till we know that our place is in the world and that our bodies emerged from this earth, we cannot know who we are.

Language too, is rooted to place, to the land. Our imagination is shaped by landscape and topography. Language can either reflect the abundance, the richness of our belonging to a complex and vital community of life or it can reflect a poverty borne of exile.

I am enthralled with the language of indigenous people. Not only does it carry a beauty in its sound, but also the words themselves reflect an unbroken arc between the speaker and his or her surroundings. In many of these languages there is no dichotomy, no separation that strands the human in a point of separation as a cold observer. When a Diné or an Inuit man or woman speak, the cosmos is imminent, not abstracted or referenced. There is seldom the separation between subject and object that we find in our English language. In most traditional speech, there is a continuity of relations that is evident within the structure of the language. The Diné or Navajo language flows in ways that keep relations between everything alive. This is hard for us to comprehend, but it is invaluable for us to know that there are other ways of knowing the world. For example, the Kalahari Bushmen possess an onomatopoetic language that is as close to the sensual world as possible, its cadences mirroring the sounds of the living earth—rain, bird calls. The complex clicks of their speech mimic the rhythms of the actual life around them so that they are constantly immersed in the surrounding terrain.

I feel a deep grief when I think about how far we have deviated from the intimacy we once knew with the earth. Sitting here along the northern coast of California while my wife gathers sweetgrass, I see a tree with a golden ladder rising from its base. A fungus has emerged from this dying elder, an enormous Monterey Pine, and this stairway arises from its decay, orchestrating a new beauty. The sun is illuminating the new growth and it offers itself to me with a radiance that makes me think of Jacob and his celestial stairway.

I have been trying to place myself back into the world, as if I could leave it! Yet, spiritually that is what my culture has taught me to do. I carry a deep conditioning shaped by two thousand years of images, stories and ideals that renders life here on earth as some form of sentence to be commuted through death. We console ourselves with the deaths of those we love by saying that they are now in a better place. The earth is to be transcended: heaven is the better world that will somehow make up for the pain and sorrow of time spent here, our final reward, as it were. I find this offensive and could never believe that the Jesus I know would have ever felt such contempt for the earth. This was the man who constantly referred to the earth, to her creatures and the growing things as examples in his teachings. This was the man who retreated to the wilderness on a number of occasions to gather himself back to himself. Nature, the wild, the world contained and held him.

The wild undoubtedly shaped our original words: imitations of animal sounds, wind, thunder, the music of ocean and river. This lustrous blend of sounds quickened the imagination of our ancestors and, as I said above, even a cursory glance at tribal language reveals a richly textured, complex syntax of metaphor and imagery deeply imbued with the surrounding world. In the Amazon, for example, language is riddled with metaphors of the jungle to express a multitude of situations and aspects in the lives of the people. Jay Griffiths writes, “Metaphor is where language is most wild, spirited and free, leaping boundaries, and it may be no surprise that Amazonian languages can be as matted and dense with metaphor as the forest is tangly with vegetation. The Amazon seems a place of boundless allusion, this unfenced wild, where meaning is twined within meaning; words couple and double, knotted together.” Our modern lexicon, however, reveals an erosion in our formerly flowering language. We are now speaking in acronyms, abbreviations, texting our words through phones and other devices. My feeling is that as our senses are deprived of the multiple cadences from a living world, so too does our language atrophy. We are left with bare rhetoric instead of a kind of speech that can bring us to tears or into symmetry with the many others with whom we share the world.

In a very real way language and place are synonymous. Words reflect what we inhabit, where we dwell. Thomas Berry said that our imagination is only as rich as the diversity of the life around us. If we inhabit a terrain of microchips, cell phones and video monitors, we speak two-dimensionally, abstractly because there is nothing sensual about these realities.

If, on the other hand, our daily round includes sunlight, fragrances from the green earth, songbirds, tastes of berries picked from the bush, then our sensual minds stir and the words become as richly textured as the terrain. Our language has an ecology and it is as varied as the experiences it is given. Jay Griffiths speaks to this in her book, Wild: An Elemental Journey, “All languages have long aspired to echo the wild world that gave them growth and many indigenous peoples say that their words for creatures are imitations of their calls. According to phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty, language ‘is the very voice of the trees, the waves, the forest.’” (pg 25. Wild)

Oral traditions are metaphorical and creative, filled with rich imagery. Stories were held in memory, that is, by heart, and the wisdom was continuous from generation to generation. We have a hard time memorizing our social security number let alone a phenologic account of a living system. What migrates when? What is ripe now? When do we relocate to the winter grounds? How do we prepare the acorns? How do we resolve conflict? How does one become a man or a woman? Stories were the carriers of this wisdom and the words used to transport the stories were alive with meaning and significance.

I want to see our words jump off the ground, erupt from a sensual earth, musty, humid, gritty. I want to taste words like honey, sweet and dripping with eternity. I want to hear words coming from my mouth and your mouth that are so beautiful that we wince with joy at their departure and arrival. I want to touch words that carry weight and substance, words that have shape and body, curve and tissue. I want to feel what we say as though the words were holy utterances surfacing from a pool where the gods drink. What if our words could once again echo the larger reality of the sacred and not solely the world of economics? But that would take an act of remembrance, a slowing downward into a state of presence, awareness and being. And this means being in the world. Enough of this talk that makes us strangers! I want to know I belong here. And if my words can say to you that I am a man of this earth, this particular piece of earth, then I will feel like I have arrived. My language must be redwood speech, watershed prayers, oak savannah, coupled in an erotic way with fog, heat, wind, rain and hills, sweetgrass and jackrabbits, wild iris and ocean current. My land is my language and only then can my longing for eloquence by granted. Until then I will fumble and fume and ache for a style of speaking that tells you who I am.